Skin Projection

- 18 Mar, 2003

The Evolution of Jae Hoon Lee

The first time I heard about Jae Hoon Lee's work was through a gallery director, who told me about this guy who was planning an exhibition that involved apples mechanically spinning in flowerpots filled with gravel. The grinding sound was going to be amplified through microphones. Cool, I thought. I can write about that.

The apples didn't happen until later. Instead the project turned into Transform, Lee's only previous solo show in New Zealand, at Auckland's George Fraser Gallery. It involved two projections, one of a male form and one of a female, both digitally created. Both figures spun in black space. The gallery was also filled with the sound of dripping water, which added a 'natural' element to the otherwise digital installation and explored Taoist ideas about the importance of water as a life force. So Transform used the human body as its starting point, giving the work a physicality not normally associated with digital art. And this is really the key to all of Lee's work. He uses contemporary technology to explore relationships. Rather than allowing machines to create distance, he sets up intimate encounters.

Almost all of Lee's work is about the body. As an undergraduate student at San Francisco Art Institute, he created large-scale installations of useless furniture. Chairs you couldn't sit on, tabletops that sloped away, that sort of thing. At Elam, he made several installations and performances, including Transform and the infamous spinning apples (the sound of the apples pretty much emptied Elam's auditorium when the piece was performed, no mean feat when you consider that it was full of sound artists and art students). He was included in Artspace's 2001 New Artist's show, Flesh and Fruity, which was the first time he showed work made from scans of his own body. Since then, he's been scanning himself every day, manipulating his flesh to create large video projections. By projecting his skin in the gallery, he explores the relationship between our bodies and space, or more to the point, the way he can affect that relationship.

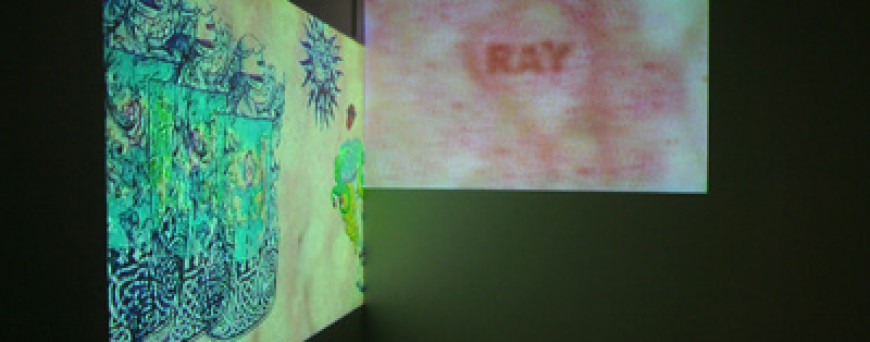

Lee's is a perverse intimacy that borders on being abject. He lies down on the scanner and lets it do its thing and the result is giant flatbed close-ups of his blotchy naked flesh. Each daily scan is numbered, with numerals that look like they've been cut into his skin. They add to the creepy sense of violation that lies at the heart of the project, a violation not just of his, but also of our space, because he makes us look at an exposed and private body. Both works in this show have a sense of some sort of injury or manipulation. On the one hand, there's Tattoo Projection, which is premised on the alteration of the body by cutting into the skin. On the other, there's Faciality, which shows a different type of penetration in that it merges the faces of several people into one long, rolling, skinscape.

Tattoo Projection is about fantasy and the fact that new technology lets us control the way we project ourselves in the world. Lee scanned his face every day for three months and wove those still images together to form a 'facial film'. So on one level it's this totally banal thing, like taking a photo of yourself, or measuring your height against the wall. But then it becomes this giant expanse of pink flesh, so that all that banal information becomes overwhelming and kind of gross. The tattoos come from the Internet. He downloads other people's tattoos (apparently the dragon belongs to a Japanese gangster) and superimposes them over his skin. As a result, they're impermanent and intangible, totally different from the real physical experience of getting one done. They're a fantasy, a way for him to change his body in cyberspace. But this 'distance' and 'safety' is negated by the inclusion of open and visible wounds. In combination with the tattoos, they provide a sense of some self-imposed physical pain, a willing injury for the sake of body decoration. In fact, these are just shaving cuts from blunt blades scraping across his face. But the dots of blood get blown up so that they become much more unsettling. The tattoos are also threaded together like an animation; obliquely suggestive of a story because of the way they're grouped. There are little 'collections' of images like angels and skeletons. There are religious symbols Hindu, Buddhist, Christian followed by a silver fern, that archetypal kiwi icon. So because of these groups it's just possible to forget that you're watching skin and start thinking that something might actually 'happen'.

For Faciality, Lee scanned the faces of his friends. There's something basic and 'everyday' about this in that our daily interactions are so determined by seeing familiar faces. But here Lee presents them on an unfamiliar scale, with a candour that would make even the least vain self-conscious blotchy close-ups of imperfect skin. So although each is named (which doubles the 'signature' element by including the name and the face), the way they roll into each other to create one long abstract surface reframes the relationships between them. Lee states that, for him, they act like flashbacks, personal memories of the real interactions he had with that person. But for us, they become divorced from a real body. As each face penetrates the next, it suggests, in Lee's words, 'a virtual intercourse' and an unsettling posthuman hybridization.

Sound is an important aspect of the installation. Lee uses it to anchor the viewer in real time, which helps create a more tangible relationship between the viewer and his projections. The main sound in Skin Projection comes from a scanner a constant grinding amplified to take over the space. It's almost loud enough to drive you out (which is what happened two years ago with the apple performance). But the rhythm of it mimics the movement of the skin. At the same time it's a reminder of the artificiality of the images that their 'moment of creation' happens inside a computer. So like the images themselves, the sound highlights the tension between technology and the body.

Lee's use of banal moments and casual intimacies complicate a simplistic reading of his treatment of the body as 'abject'. In Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva describes abjection as:

- ...a revolt of the person against an external menace from which one wants to keep oneself at a distance, but of which one has the impression that it is not only an external menace but that it may menace us from inside. So it is a desire for separation, for becoming autonomous and also the feeling of an impossibility of doing so...

Lee's work does seem to fit this. At times it's revolting. Giant shaving rash, skin discoloration and errant hairs are never nice to look at. And at times it's menacing, a response brought about by the scale of his body versus our own. But the abject is something we're simultaneously repulsed by and drawn to. Lee's tattoos and half-healed sores have this quality. Watching them is like picking a scab, something gross but irresistible.

There's a narcissistic aspect to Lee, in that he both objectifies himself but also imposes his reflection on us. He tries to overwhelm us with his body. His narcissism is acted out on a flatbed scanner, which means he's literally pressed up against it. We don't have any distance from his flesh. His is pressed up to ours in black space, yet another part of the weird sensuality that pervades the work. As a result, the size of his projections creates an abject Sublime, a kind of beautiful, degrading and degraded posthuman body. But the banality of their production, the diaristic tracing of self over a prolonged period, suggests that he might just be trying to show us his daily experience. So he cuts himself shaving from time to time. There's nothing special in that. Or maybe there is, in and age when new technology and mass media increasingly distance us from physical experience. Instead of relying on the rhetoric of new technology, Lee explores fundamental themes about intimacy and our reliance on our bodies to translate and normalise daily rituals and interactions.

In Transform, I described Lee's work as being 'as mythic as it is mechanical'. This still holds true for Skin Projection. Despite his use of technology, he deals with old issues sex, death, our bodies, the Sublime. He tests his own limits and the limits of the space, so that his skin becomes a total environment. Digital art is often criticised for being too distant, it's cybernetic sterility stripping away any chance of a visceral response. But Lee's is different. It's about desire, ritual and real relationships. The evolution of Jae Hoon Lee is a strange, perverse thing to watch. In an email to me, he wrote that: 'We may unconsciously project our sensational ecstasy via the flesh of our human existence.' I like this idea. It sounds cool. Just like the apples did.

Anthony Byrt, March 2003.