To Pluck Water

- 25 Jul - 8 Aug, 2012

To Pluck Water

One of the most common (and most true) criticisms leveled at contemporary art today is for its aloofness, a prescribed coolness that seems to purposefully alienates its audience requiring a level of translation that most ‘non art’ gallery goers don’t have the patience for. The biggest losers to this new cool (aside from the audience) seem to be artists motivated by the every day issues, big and small, that define who we are and where and how we live. Strangely the art world seems to get squeamish the closer we get to an accurate reflection of the world we live in, as if without the smoke and mirrors the slight of hand might be revealed and the art world will be shown for the fool.

The opposite can be true, art that gets us up close to the stuff and grit of life, can communicate the mystery and strangeness of being human best when we can recognize ourselves in it. Wellington based artist Murray Hewitt’s back catalogue of video works are filled with places and people that we recognize; suburban landscapes, petrol stations and rugby fields all feature, a lone costumed male figure reoccurs as do emptied out New Zealand landscapes. He uses the simplicity and power of the moving image to talk about everyday things (big and small), his work is often both funny and disquieting, wry commentaries on day-to-day life from the trivial to the political. In Hewitt’s 2010 work Recessional, seemingly un-monumental landscapes - rural churches and modest civic memorials - are filmed in static, single shot takes, 61 sites in total, each one a historical battle site where Māori and the Crown fought and where life was lost. Recessional is simple and understated, a renewed epitaph for those who died and a stark marker of progress (or the lack of) regarding issues of land rights and self-governance for Māori today.

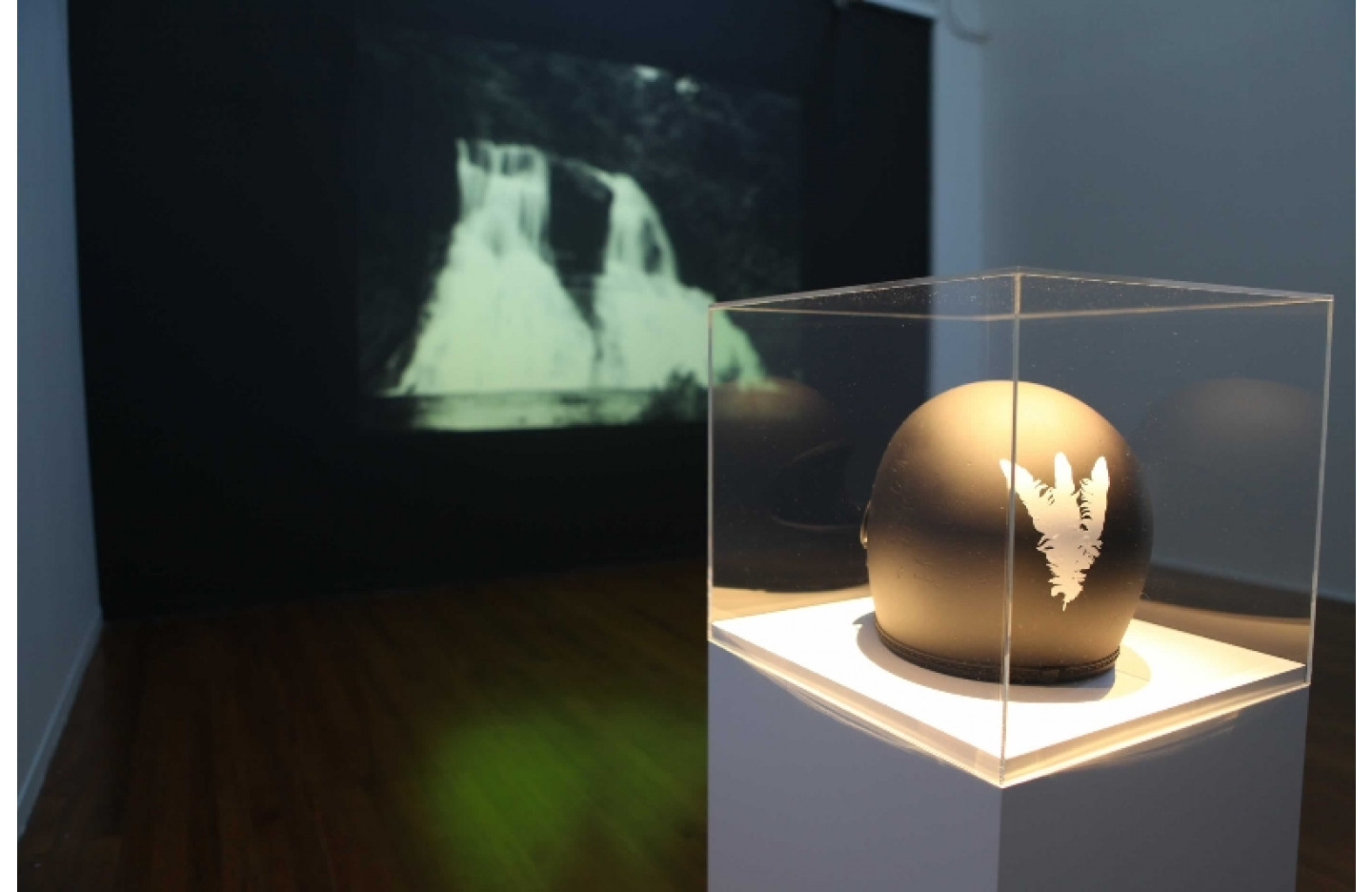

To Pluck Water brings together two of Hewitt’s recent video works, projected in the main gallery U.D.N.R.A takes us to 7 waterfalls in the Urewera National Park, again with the single static shot. Like with Recessional there is a striking contrast between the emptiness and simplicity of how the site is presented and the complex cultural histories, personal connections and political controversies present in the ‘place’. The black and white image plays in reverse, water defies gravity and runs haltingly up the cliff face in an endless return to the source. Transforming the simple act of looking at water, it’s the feeling of momentarily not recognising something you’ve seen a thousand times before. The title of the work references the Urewera District Native Reserve Act 1896, the result of a negotiated agreement between the Crown and Māori leaders of the Urewera region. The act was designed to recognise real powers of self-governance to be exercised by the peoples of Te Urewera. The potential for the Act to reinstate autonomy and self-determination to the Tuhoe people was never realized and the act was repealed in 1922.

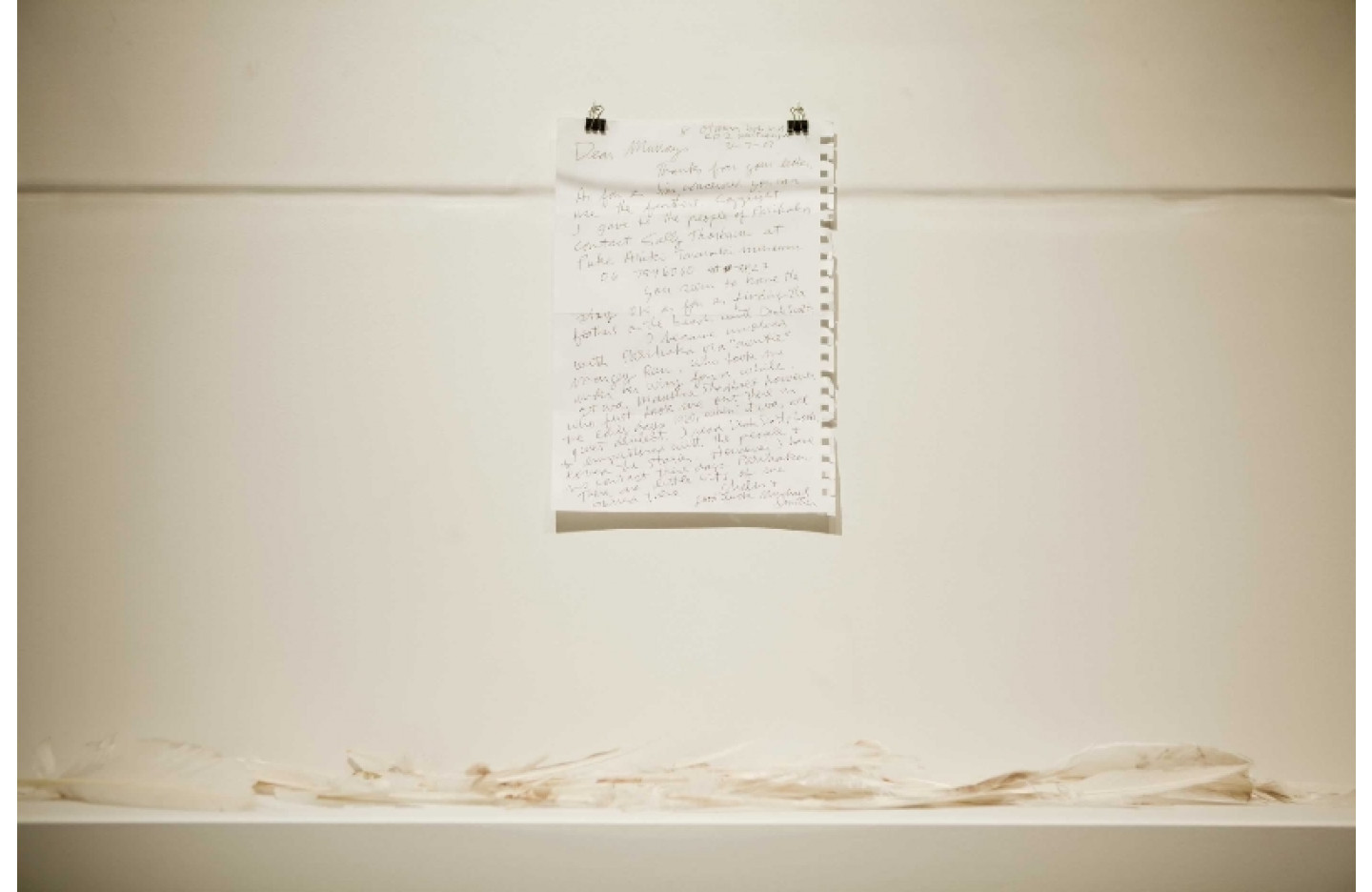

Weeping Waters documents a lone male figure repeatedly kicking a soccer ball up the steep face of a sand dune on an unidentified New Zealand foreshore; the work is described as an endurance performance marking the 100th anniversary on the passing of the prophet Te Whiti O Rongomai of Parihaka. After watching for several minutes we remember the heat of the beach and the heavy gravity of running on sand, but the figure makes no spectacle of his effort, exercising quiet futile persistence. He wears a black motorcycle helmet, the back of the helmet bears the Raukura symbol, three albatross feathers signifying peace and goodwill left for all people by the prophets Te Whiti O Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi of Parihaka. Bronwyn Holloway-Smith’s essay Peace May Reign describes her and Hewitt’s visit to Parihaka in 2007 in order for Hewitt to seek permission to use the symbol in his video work. It sounds like a daunting process and Hewitt is rewarded for his commitment to following it through.

The motorcycle helmet is displayed alongside the video works contrasting the seemingly simple act that plays out in Weeping Waters with the weight of the responsibility for the artist, of obtaining permission and then using the Raukura as a symbol in the work. The use of the plinth and case to display the object restates the Raukura as a Taonga, a legacy left for all people.

(Kim Paton, 2012 - Curator: RAMP Gallery)

About the artist:

Murray Hewitt mostly works in video. With a distinct visual language his works have contemplated consumer behavior, remembered historic events, or mulled over current political ones: through the considered actions of a lone costumed figure, or repetitive stationary camera shots that encourage sustained deliberation from the viewer.

Murray Hewitt is a first generation New Zealander, his parents immigrated in the 1960’s from England, he now lives in Moera in Lower Hutt.

He finished a Masters degree in Fine Arts from Massey University in 2007. He also has a NZ Certificate in Civil Engineering and worked for many years as a youth worker. He currently works as an art installer for a number of galleries in Wellington and also picture frames a couple of days a week when not installing.

The essay Peace May Reign by Bronwyn Holloway-Smith is also available in the gallery.

Murray Hewitt is associated with the newly formed arts agency called CIRCUIT Artist Film and Video Aotearoa, who are supported by CNZ to distribute video by local artists. CIRCUIT has an extensive list of Murray's videos you can see here . View a video interview with Murray is here