Two New York Works

- 30 Sep - 17 Oct, 2003

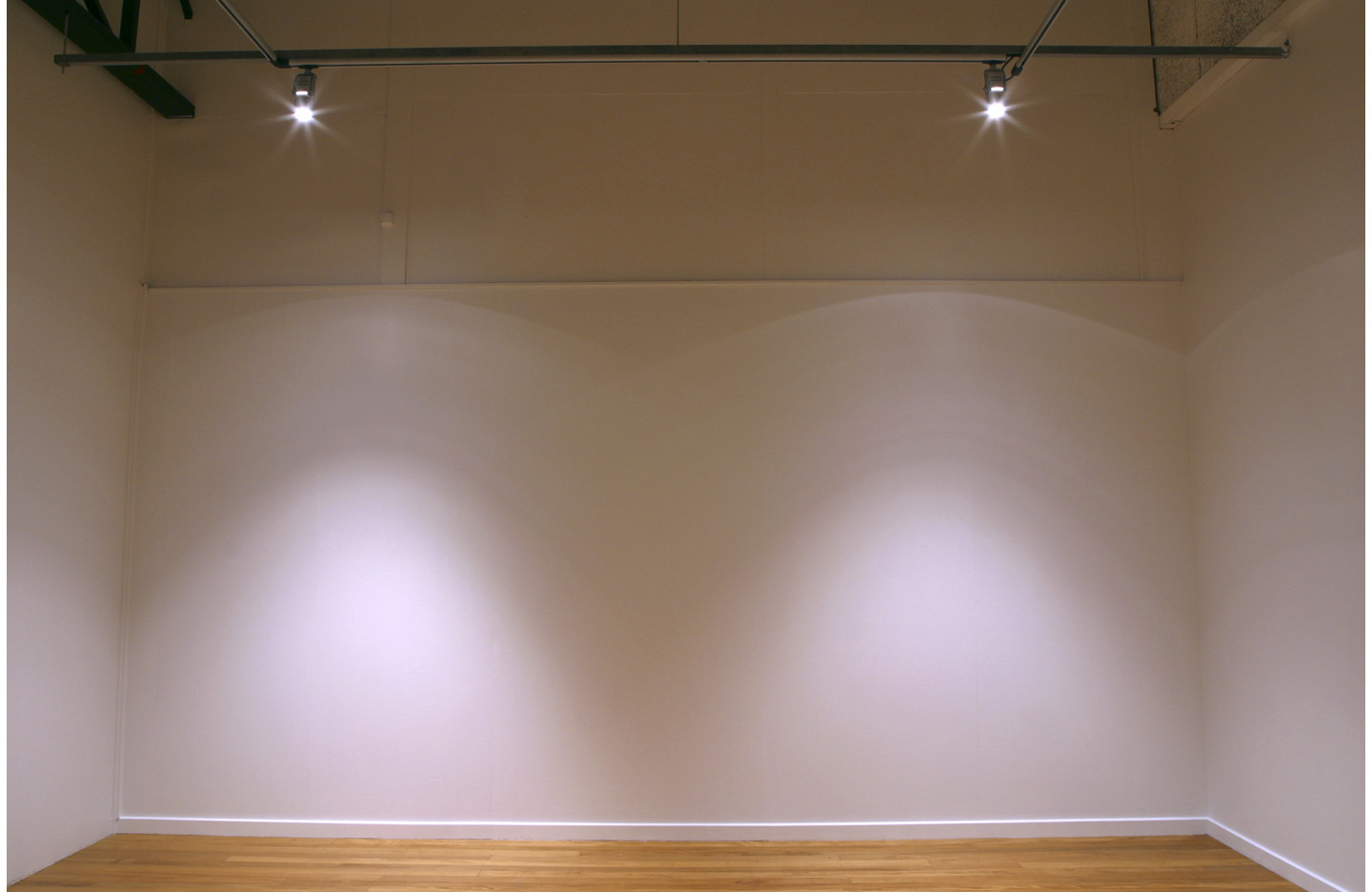

Four Spotlights, Apple, 1969

Extension of the given, Leo Castelli Gallery, 1977

Installed as Four Spotlights, Ramp 2003 and Subtraction from the given (internal entrance), Ramp 2003.

Billy Apple is New Zealand's most important conceptual artist. In a statement as simple and as declarative as this, there are two major issues. The first relates to the question of 'New Zealand-ness'. Often, important New Zealand art is thought of in terms of its response to 'our place', to the specific contingencies of our own geography and social experience. Apple's work has never been concerned with such things. The second relates to the notion of 'conceptual art'. At the heart of conceptual art, initially at least, was an interest in breaking the hegemony of the gallery system in the United States. Conceptual artists sought to dismantle the 'white cube' model and its canonisation of modernist abstraction, and force audiences to think about art beyond formalist aesthetics. Apple was a significant figure within this, and throughout his career has continued to address issues of 'space' and the gallery system. This installation at Ramp is a part of that continued project, a part of his examination of the way we view and discuss contemporary art.

Two New York Works recreates conceptual pieces Apple made while living in New York. Four Spotlights was the first work he presented at Apple, the artist-run space he established at 161 West 23rd Street in 1969. Subtraction from the given (internal entrance) recreates a work he made at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1977. In both, there is a challenge to the audience, a questioning of their gallery-going expectations, because the gallery itself is the art. Ramp's architecture determines the final forms of the works. The effect of this is that in a sense, these are not historical works at all, but completely new works based on earlier ideas. This unusual jump between time and space (both 'then and now' and 'there and here') raises questions about relations between the historical and the contemporary, questions that can also be raised about Apple's position as an artist.

To better understand how we might address such questions, a brief overview of his career is needed. After a series of trips beginning in 1961, he moved permanently to New York in 1964 and was a leading figure in the emergence of conceptual and performance art. Both these new practices began to radically re-negotiate questions of 'site' and 'audience' by addressing issues such as time, the body and site-specificity. T support such work, artist-run spaces emerged as an alternative to the dealer-museum system, which was seen as unable and unwilling to accurately represent the concerns of these new artists. Apple founded New York's second artist-run space, his self-named gallery Apple, in 1969. As well as establishing this venue, he continued to produce art that contributed significantly to the new environment. Among his best known works from this period are his Subtractions, or cleaning pieces. Whether scrubbing a gallery floor, cleaning windows, collecting broken glass, or documenting bodily functions, these performances acted as diaristic responses to his own experiences, as subtle interventions in the spaces he worked and lived in.

The subtlety of his cleaning interventions was made more permanent when he returned to New Zealand in the late seventies for his Alterations series. He carried out a number of alterations to prominent institutions including the Auckland City Art Gallery and the Robert McDougall Gallery in Christchurch. Perhaps the most visible today is his alteration to the staircase of New Plymouth's Govett-Brewster Gallery, in which he widened the top flight by half its original width. Apple's tour was a defining moment in raising the stakes for New Zealand conceptualism. During the seventies, 'post-object' sculpture had introduced aspects of installation and new media practices into New Zealand art, though its primary emphasis was on sound and performance. In contrast, Apple's tour and its substantial documentation by Wystan Curnow in Art New Zealand 15, introduced local audiences to the critical acuity of New York conceptual practice.

Since then, he has worked with a number of galleries, at both institutional and artist-run levels, and most of his projects have directly addressed his relationships with those spaces or critiqued the way the art market works. For instance, he was the first artist to show at Artspace's George Fraser Gallery in 1987, where he presented hisTransactions, a major series of works that examined the various means of commodity exchange in art. In the last decade or so, he has collaborated with younger artists and has been consistently involved with new contemporary art galleries such as Teststrip, 23A, rm401, The High Street Project, and now Ramp, all of which are non-institutional project spaces that have sought to support emergent artists.

So in this context, the Ramp exhibition starts to gain some momentum. We can look historically and see the cleaning interventions, the Alterations, the Transactions, and of course in this show, one of the Extensions, inverted as aSubtraction. Implied in all these related words is a rigorous examination of art's infrastructural conditions. This is clearly shown by Subtraction from the given (internal entrance). The arc of Ramp's open door is carefully established by drawing a line from the back of the door to its opposite corner. The door is then fixed in this position, and the open arc is painted white, the same white as the door. Thus the title becomes explanatory. Apple's intervention is a subtraction from the conditions he is given as an artist and that we are given as an audience. He takes away part of the gallery. The open arc is 61.3 degrees. An awareness of such details is crucial to his statistical and conceptual framework and such precision is a defining feature of his practice. At the far end of the room, two architectural drawings are mounted on the wall. One is the original invitation to the Leo Castelli installation in 1977 and next to it is the remarkably similar drawing of Ramp. It's important to note however, that the Ramp work is a reversal (a subtraction rather than an extension) of the original. But despite the fact that they are technically 'opposite', there is only a matter of a few degrees between the two, suggesting at once a nostalgia for the Castelli work, as well as an interesting parallel for Ramp, an architectural detail which links it to one of the most important dealer galleries of the twentieth century. So this doubling creates a dynamic, discursive relationship between the two shows. Though separated by twenty-six years, Apple's recreation puts them in conversation with each other.

In the main gallery is Four Spotlights. Like Subtraction from the given, the title says it all. Four of Ramp's spotlights form a square, all pointing directly down at the floor. Consequently, the contingencies of the space itself are thrown into focus. The invitation to the exhibition is a scale drawing of these lights. The space has been 'detailed' so that it is as clean as possible. The floor has been polished, edges have been sharpened, stray drips of paint have been sanded away. It becomes a pure starting point for an exhibition, but in this case that starting point is the exhibition itself. And there are also questions about what, or where, the actual artwork is. It could be the recreation of the earlier work, or it could be the lights, or it could be the floor illuminated by the lights, or it could be the fact that the floor is illuminated by the lights. Once again, all these possibilities suggest connections between 'then and now', between two works separated by time that end up occupying the same space.

So what we have with Apple's conceptual works is a subtraction of 'things', an absence of physical objects, as such. As a result, rather than looking at retrospective artifacts, we're actually looking at the re-articulation of ideas, ideas that force us to think more carefully about art's conditions. It's interesting in relation to these questions of the historical and the contemporary to look at the influence Apple has had on a current generation of artists who similarly explore installation and performance as a means to critique the gallery system.

In 2001, Martin Creed won the Turner Prize with a work that consisted of a light bulb switching on and off in a gallery, a work which is ostensibly based on the same concerns as Apple's Four Spotlights. In another eerily familiar moment, Creed produced Work No.115: A doorstop fixed to a floor to let a door open only 45 degrees, a seeming reference to Apple's Extension of the givenseries. Its matter-of-fact, descriptive title makes the connection seem even stronger. But in both cases, no acknowledgment was made by Creed of Apple's work. Such referencing, or lack of, raises issues for conceptual art about 'intellectual territory'. Without the production of tangible objects and due to the distinctly different conditions within which the works are produced and reproduced, Creed's conceptual relationship to Apple walks a fine line between the discursive and the plagiaristic.

More locally, there are two artists in particular whose works show a clear homage to Apple's. One of the interesting features of conceptual art is that if there's no artifact sitting in a museum, the work won't gather dust, literally or metaphorically. But one of New Zealand's best young artists, Dane Mitchell, does exactly that. Gathers dust in museums. Not him. Well, kind of him. Mitchell collects dust samples from institutions in Europe and Australasia and collaborates with a microbiologist to culture them into bacteria. This has resulted in some infamous examples, like the Auckland Art Gallery, the dust of which contains an organism that causes urinary tract infections. Unearthing these icky biological histories in our most pristine cultural reservoirs clearly owes something to Apple, whose performances and gallery interventions similarly use collection as a means to examine institutional art-politics. Like Apple's work, Mitchell's is statistically obsessive and demonstrates that stripping, rather than employing metaphor, can create eloquent and unnerving statements about our relationships with gallery spaces.

Another of New Zealand's most important young artists, Daniel Malone, recently had a survey at Artspace. In it, several of his works made direct reference to Apple. This is no clearer than in ??? (check Who Do I Think I Am catalogue), in which Malone changed his name by Deed Poll to Billy Apple, re-enacting Apple's own eponymous artwork, his 1962 name-change. Then for Malone's exhibition, Apple himself recreated a Subtraction, by erasing Malone's 'tag' from the side of Artspace's sign. Photographs of Apple cleaning it away were shown alongside the official notification of Malone's name-change. So in a gesture as simple as this cleaning, issues of branding, identity, performance and intervention are all raised.

But this didn't just repeat Apple's seventies cleaning works. It also re-enacted a previous re-enactment. In 1996 Apple and others performed a cleaning work to open Teststrip's second space. Malone was one of the founding members of Teststrip, New Zealand's most important artist-run space of the last decade. Further, Teststrip was to a certain extent the inheritor of the alternative gallery system that developed between 1969 and 1975 in New York, which, as mentioned above, Apple had a big hand in. So again, like the relationships in Ramp and with Creed and Mitchell, these relationships between Malone, Teststrip, Artspace and Apple become discursive points in which a range of historical moments are brought together.

So we end up back at Ramp, in an almost empty gallery. But there's a weight of art history and art discourse in Apple's installation. It throws the space into focus, but more than that, it throws our history of conceptual art into light as well. Apple's work represents a crucial point in contemporary New Zealand art. As an artist who was actively involved in New York conceptualism, he is a crucial link between 'here and there'. His work has provided a model for explorations of the role of the artist, the role of the gallery, and the function of art in a post-conceptual environment, themes that are constantly revisited by artists who examine the complex relationships between 'idea' and 'commodity'. His interventions in galleries, including this one, cause us to revise our attitudes towards those spaces. His art continues to challenge and to contribute. Whether it's historical or contemporary doesn't matter.

And all this from a few spotlights and an open door.

Anthony Byrt, September 2003.